Western

Today, we’re going to talk about temporomandibular joint dysfunction—often abbreviated as TMJ or TMD. TMJ refers simply to the temporomandibular joint, while TMD stands for temporomandibular joint disorder or dysfunction.

Basically, TMJ disorder affects the jaw joints and the muscles around them. These joints are located on both sides of your face, right in front of your ears, connecting your jawbone to your skull. They allow you to open and close your mouth so you can eat, speak, and chew.

TMJ disorder is surprisingly common—about 5 to 10% of adults experience some level of this condition. It tends to show up more in women and is most often seen in people between the ages of 20 and 40. The symptoms can vary from person to person, but you’ll typically notice jaw pain, facial pain, stiffness, and sometimes difficulty opening or closing your mouth. A popping or clicking sound when you move your jaw, along with headaches, earaches, or even toothaches, can also be part of the picture.

From a Western standpoint, there isn’t a single clearly defined cause for TMJ dysfunction. Experts suggest that prior jaw injuries, teeth grinding, arthritis, or even malocclusion (when your teeth don’t fit together properly) could be contributing factors. Treatment usually focuses on managing pain using medications like Tylenol or ibuprofen, muscle relaxants, or non-surgical options. Many people find relief with mouth guards or dental appliances like oral splints to reduce grinding and clenching. Physical therapy is another common approach, while more severe cases might call for trigger point injections—with steroids or Botox—or even surgery, though that’s usually a last resort.

Eastern

I want to spend the bulk of our time today talking about temporal mandibular disorders from an eastern perspective and specifically acupuncture in Chinese and medicine. That’s what most of you are here for. The first thing that we need to understand is the anatomy of the meridians in Chinese medicine and how those meridians flow through the jaw come a control the jaw and lead to health and disease.

Jaw Meridians

Now to understand jaw disorders and temporal manipular disorders we need to have a good understanding of the anatomy for the Chinese medicine perspective. Now from the western perspective we talked about this already briefly, but the Chinese medicine anatomy perspective is much different. In Chinese medicine what we’re really looking at is the acupuncture channels come where they flow come which organs they’re associated and with their role is.

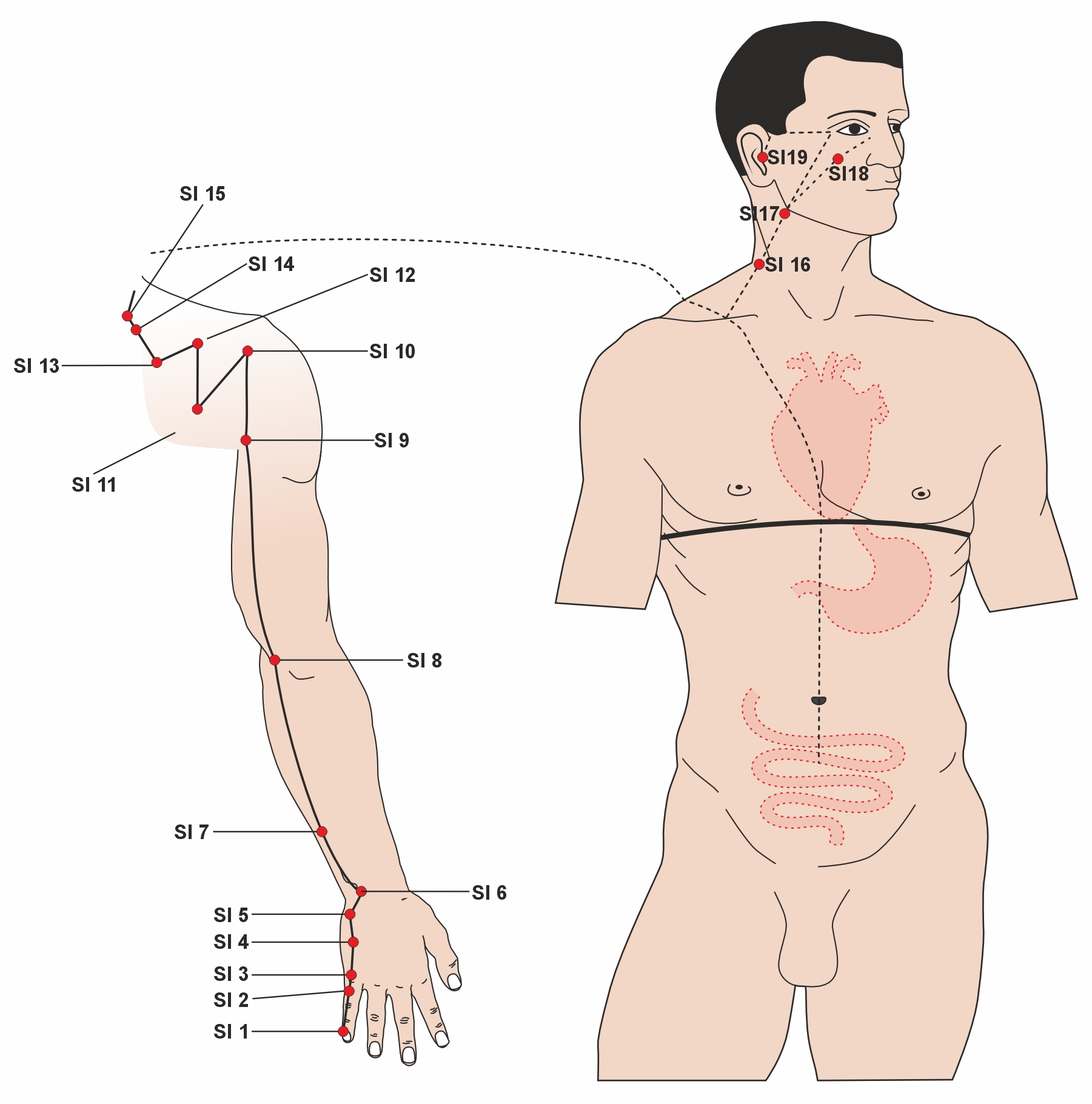

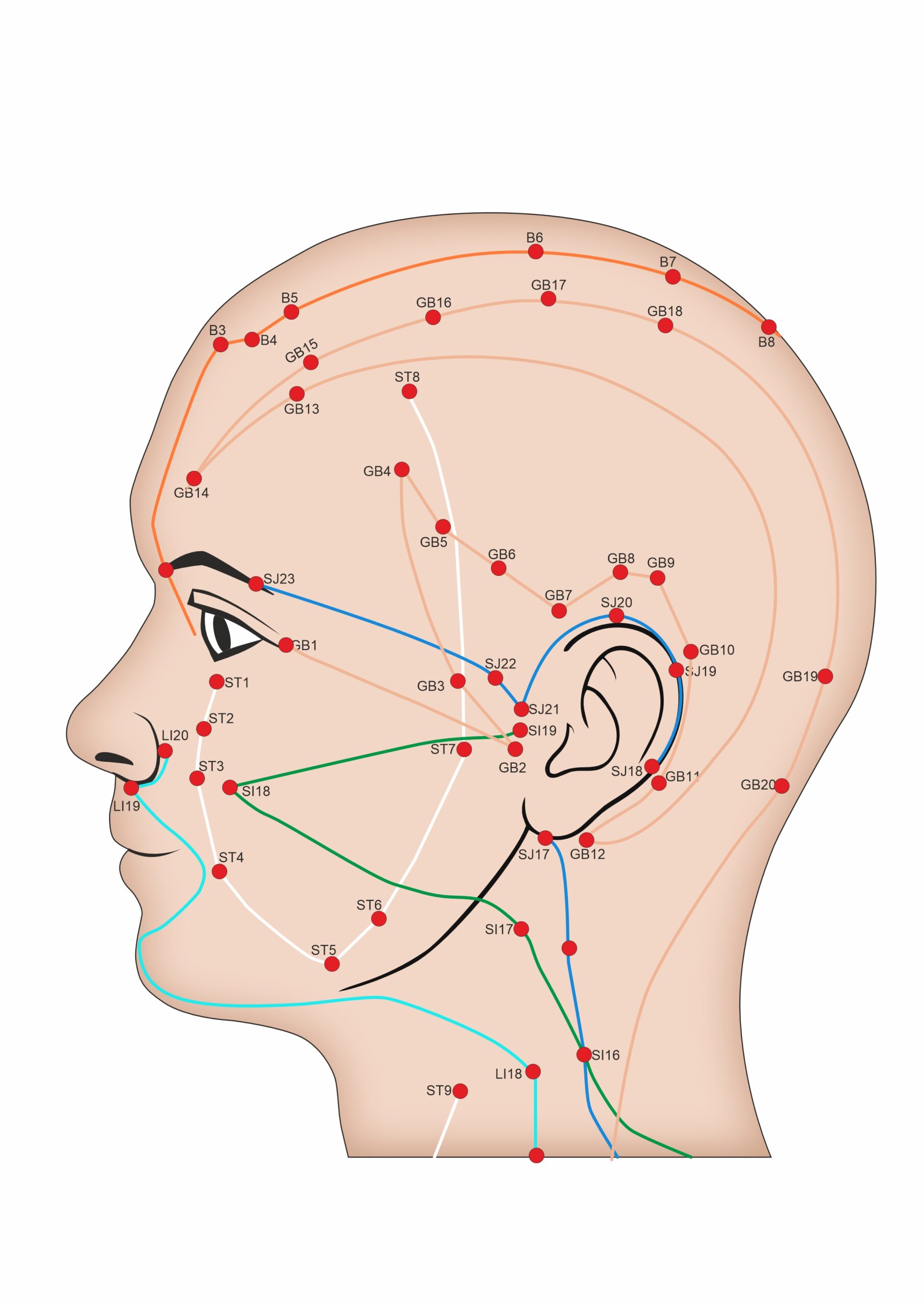

Now there’s four primary channels that supply the jaw and especially the TMJ. There’s three in particular but there’s also the stomach channel which plays a big role in Jaw motion. The 4 primary channels are the gallbladder, the small intestine, the sand jiao (or triple warmer) and the stomach channel. Now I’m going to show you guys an image of the lateral side of the head and the jaw region specifically to help illustrate what these channels look like in acupuncture. So you can see where they run and what their unique role is in the temporal manipular joint and treating temporary joint disorders.

Now the point of me showing you this chart is not because I expect you to write these down and tell your patients where it had massage, but rather it’s more for me to help illustrate to you the rationale behind Chinese medicine and how we think about disorders. What I want you to really see is that when we Talk about temporal manipular joint disorders in Chinese medicine we’re referring to much more than just a simple joint problem. What I want you to see is that the internal organs of the body are intricately tied to the health of the whole body and the TMJ is just one example of this. So if you look closely at this chart right here is approximately the location of the temporal mandibular joint. You can see that there are three different colored channels that come to focus right on this point. Upper channel or the blue colored line is blue triple warmer or San Jao Channel . That the green light bars out the small intestine channel in fact the small intestine channel has its final point right on the temporal ventricular joint and right below that the lowest of this trifecta of coins is the gallbladder meridian and that’s the brown line that you see here. Just using TMJ as an example you can see here that the organ of the stomach, the gallbladder, the small intestine Are all related to this joint and any problem in any of those organs or the channels they control can cause temporal mandibular joint symptoms and disorders.

Now you’re not going to be able to walk out of here knowing how to treat a patient with acupuncture for TMJ disorders. Come with my main purpose is to illustrate for you how I think about these disorders and what we look for when we’re treating patients. Now come up one of the coven misunderstandings about acupuncture and about Chinese medicine is people think that the acupuncture channels simply run along the anatomical neural pathways or vascular pathways that we already know about in list or medicine. But as you can see in this chart, there’s no nerve or arteries or veins that run in any of these patterns as you can see. So the idea to think that the meridians are simply nerve pathways or vascular pathways is completely incorrect. These are specifically acupuncture meridians they may occasionally associate with different nerves or vascular bodies in the body colored just as they normally associate with various organ systems come up with there is no underlying mechanism either in the neurologic system or the vascular system to explain the acupuncture pathways.

About Meridians And The Internal Organs

Let’s discuss the relationship between the meridians and the internal organs in Chinese medicine. As you can see from the chart I just showed you, there are multiple organs listed, such as the large intestine, small intestine, San Jiao (triple warmer), and gallbladder. You might look at this chart and wonder: What does the gallbladder have to do with the line running along the side of the head? Isn’t the gallbladder located in the abdomen near the liver? Similarly, what does the stomach channel have to do with the stomach itself? The stomach is located in the abdomen, just beneath the diaphragm. So, what connection does this line, shown running up the face in the chart, have with the stomach?

This relationship reflects the interconnected nature of the meridians and internal organs in Chinese medicine. Each internal organ is associated with a meridian that travels throughout the body. Chinese medicine recognizes 12 internal organs, each linked to a specific pathway that traverses the body. Six pathways travel between the head and the arms, while the other six extend between the head and the feet. Collectively, these form the 12 meridians, which correspond to the 12 organs.

The meridians have two levels: superficial, which lies on the surface of the body, and deep, which runs internally. Acupuncture points, located on the superficial meridians, are used to bring about changes in health. These meridians connect to their associated organs and interact with other meridians, forming an interconnected canal system throughout the body. This system links all the organs and contributes to a holistic view of the human body.

Because the meridians are connected to their respective internal organs, diseases affecting specific anatomical areas, such as the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), should be understood in relation to the organ systems that support those areas. For example, Chinese medicine examines anatomical problems by considering the organ channels running through the affected location, rather than focusing solely on the local area as Western allopathic medicine might.

In Western medicine, TMJ issues are typically attributed to problems with the mandible, temporomandibular ligament, joint capsule, or nearby structures. However, in Chinese medicine, specific anatomical problems are viewed holistically. They are associated with the organ channels that traverse the area and the health of those organs. This perspective encourages a broader, interconnected understanding of health.

The TMJ is not just the mandible, temporal bone, or joint articulation, – it represents a much larger concept in Chinese medicine. Treatment plans are designed based on the organ channels related to the point of interest, as in our example here of TMJ. Acupuncture points selected may be local, around the joint, or distal from it. For example, points on the leg may be used to affect the gallbladder or stomach channels, while points on the hand or forearm may influence the small intestine. The goal is to treat the organs and meridians to bring about change at the affected anatomical site.

About Qi and Blood (maybe just for dental talk)

We previously touched on the concept of meridians. The meridians are channels that carry the qi and blood of the organs throughout the body. They balance the qi and blood among the organs, allowing a natural, harmonious process to occur when the channels are open. When the qi and blood can flow freely, optimal health is maintained.

Let’s now discuss qi and blood in a bit more detail, as this is crucial to understanding how Chinese medicine views both health and disease. Additionally, I will offer a brief introduction to the way we think in Chinese medicine.

We are all somewhat familiar with the concept of blood from a Western medical perspective. In Western medicine, blood is the red substance that flows through our arteries and veins. It carries hemoglobin and oxygen to various organs, playing a vital role in sustaining life. Most of us already understand this basic concept of blood.

In Chinese medicine, we also have the term “xue,” which translates to “blood.” While the concept is similar, it is not identical. Xue, or blood, in Chinese medicine refers to nutritive energy within the body. In Western terms, we think of blood as a nutritive substance, which aligns with the concept of xue in Chinese medicine. However, there are distinctions.

In Chinese medicine, blood is viewed as a “formed substance.” It represents the nutritive energy that provides muscles with the sustenance they need to grow and remain healthy. This contrasts with the concept of qi in the body.

Qi is the active energy, or the energy of function. While xue, or blood, represents the nutritive energy—the substance that gives form to the organs and the body—qi represents the energy that drives function. Qi enables movement and activity within the organs and the body as a whole.

Together, these two forms of energy—xue (blood) and qi (active energy)—reflect the yin and yang of the body. Blood (xue) embodies the yin, or the nourishing, substantive aspect, while qi represents the yang, the dynamic, functional aspect. This broad categorization offers a holistic view of the body’s energy dynamics.

Things That Can Go Wrong With Those Meridians

These definitions of qi and blood are not exhaustive but rather broad generalizations aimed at providing a foundational understanding. For our discussion today, the primary takeaway is that qi and blood flow through the meridians. When they flow smoothly and abundantly, the individual experiences good health. However, when either of these energies becomes deficient, blocked, excessive, or imbalanced relative to the other, disease arises.

The Function And Character Of Those Meridians

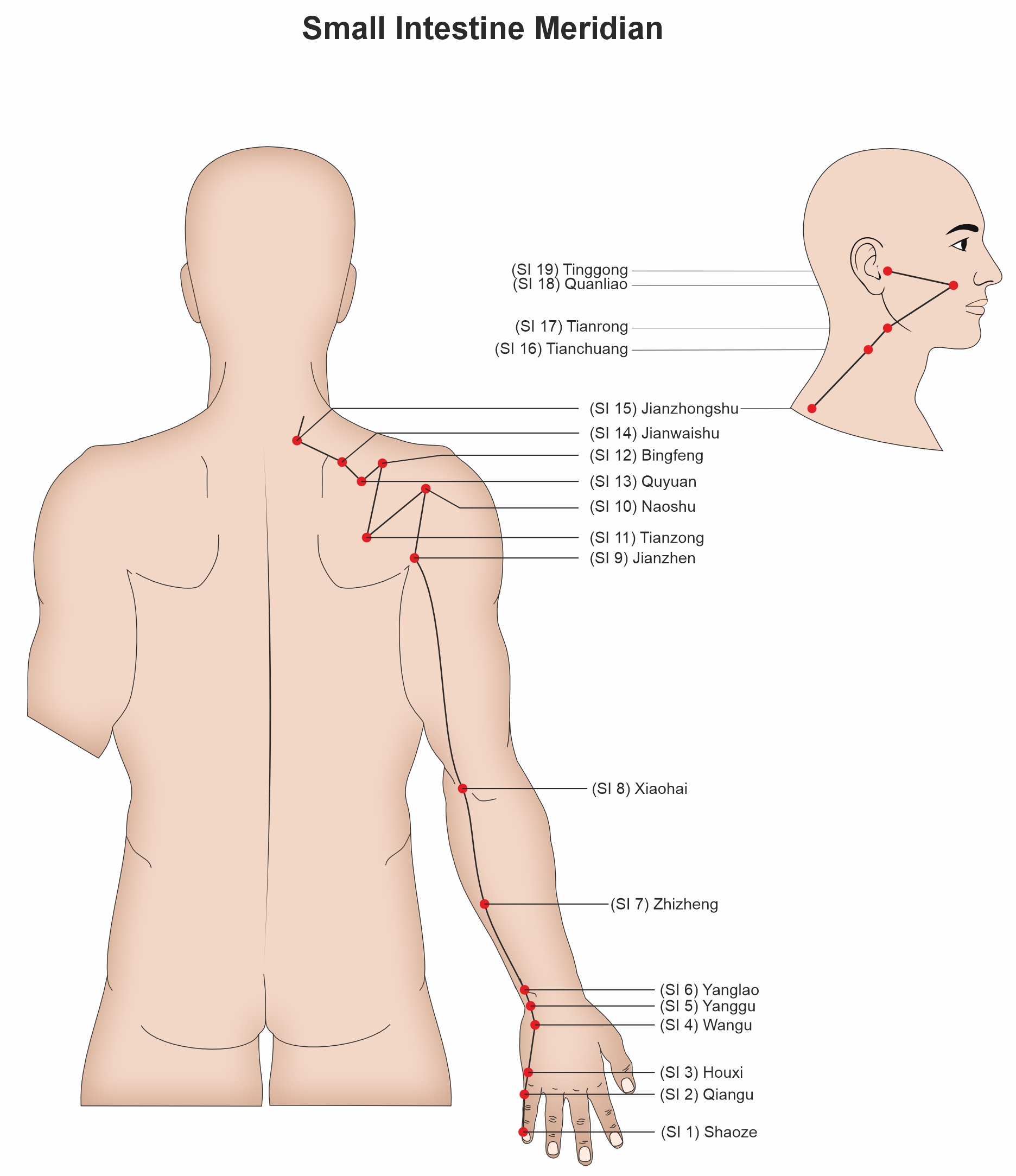

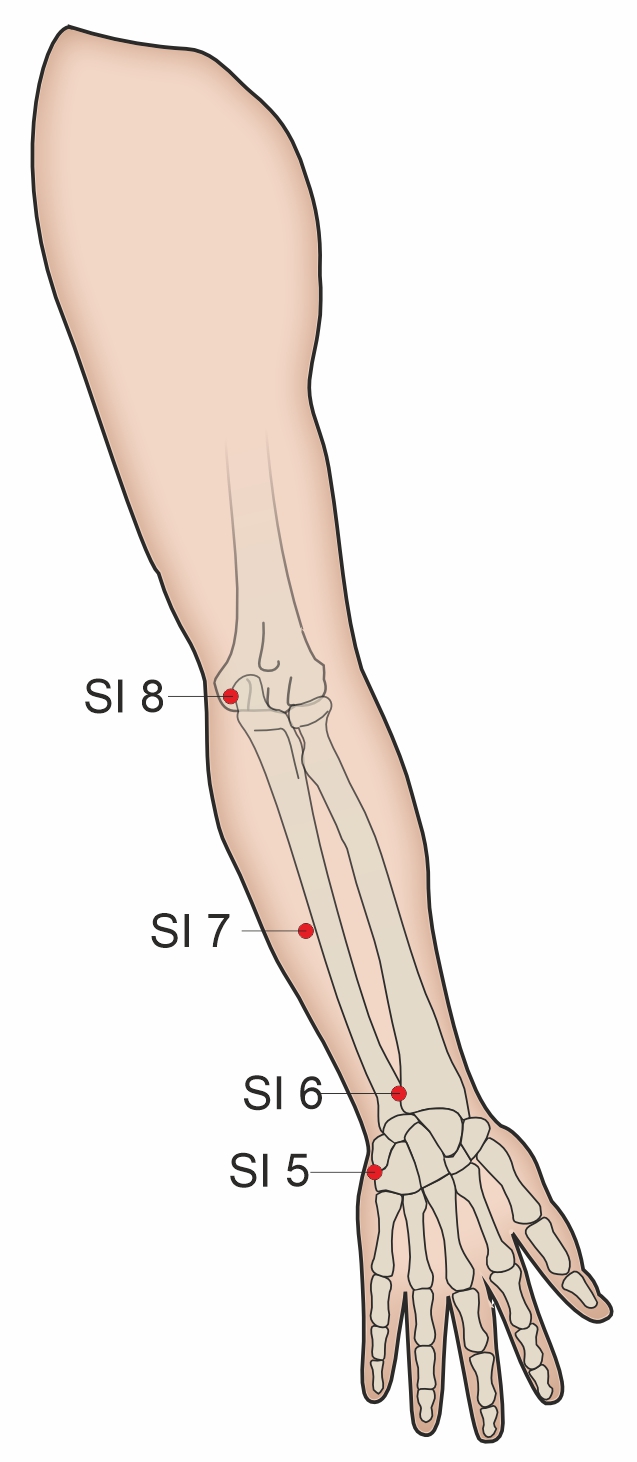

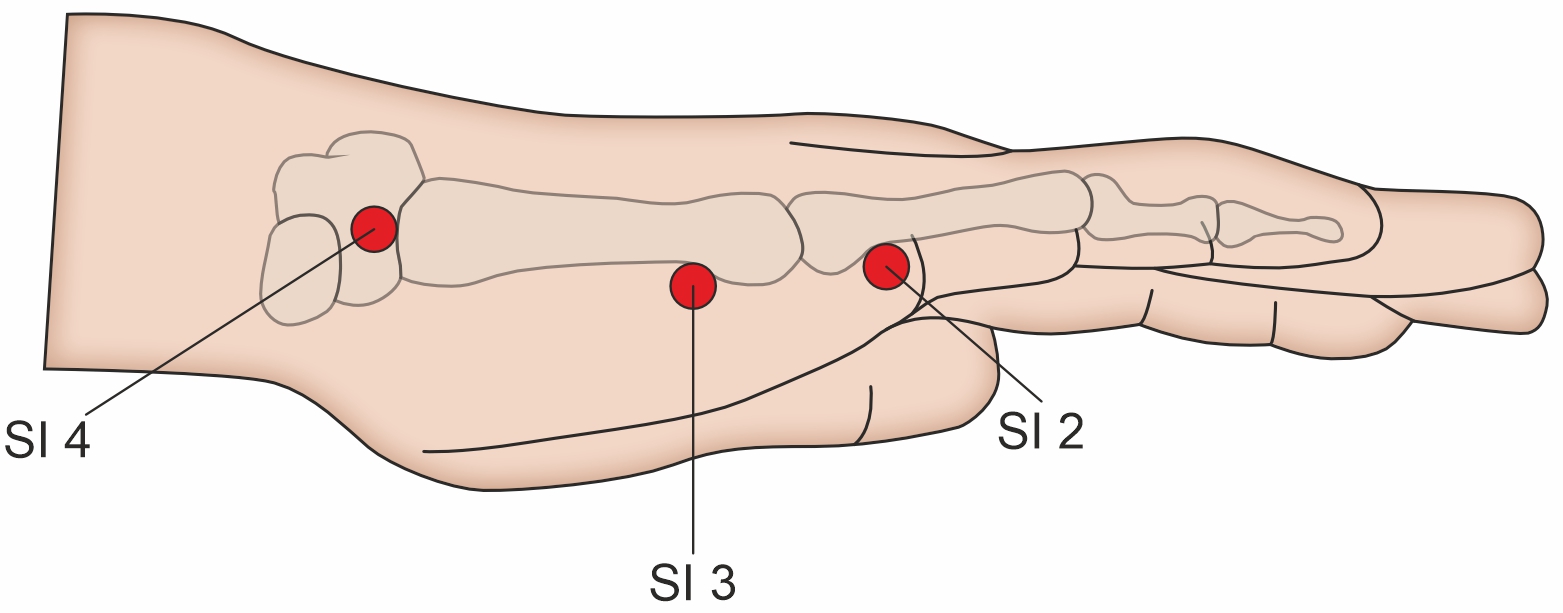

I’ve talked a little about what the meridians are and the qi and blood that flow through them. Next, I want to give an example of the course of a meridian. For this, I’ll use the Small Intestine Meridian as an example.

If you recall from the previous chart I showed, multiple meridians are involved in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ)—including the Gallbladder, San Jiao, Small Intestine, and Stomach channels. But for the purpose of illustration, I’ll focus on the Small Intestine Meridian. I want you to see what a meridian looks like, how it connects with the organs and different parts of the body, and how this helps us build a deeper understanding of Chinese medical physiology.

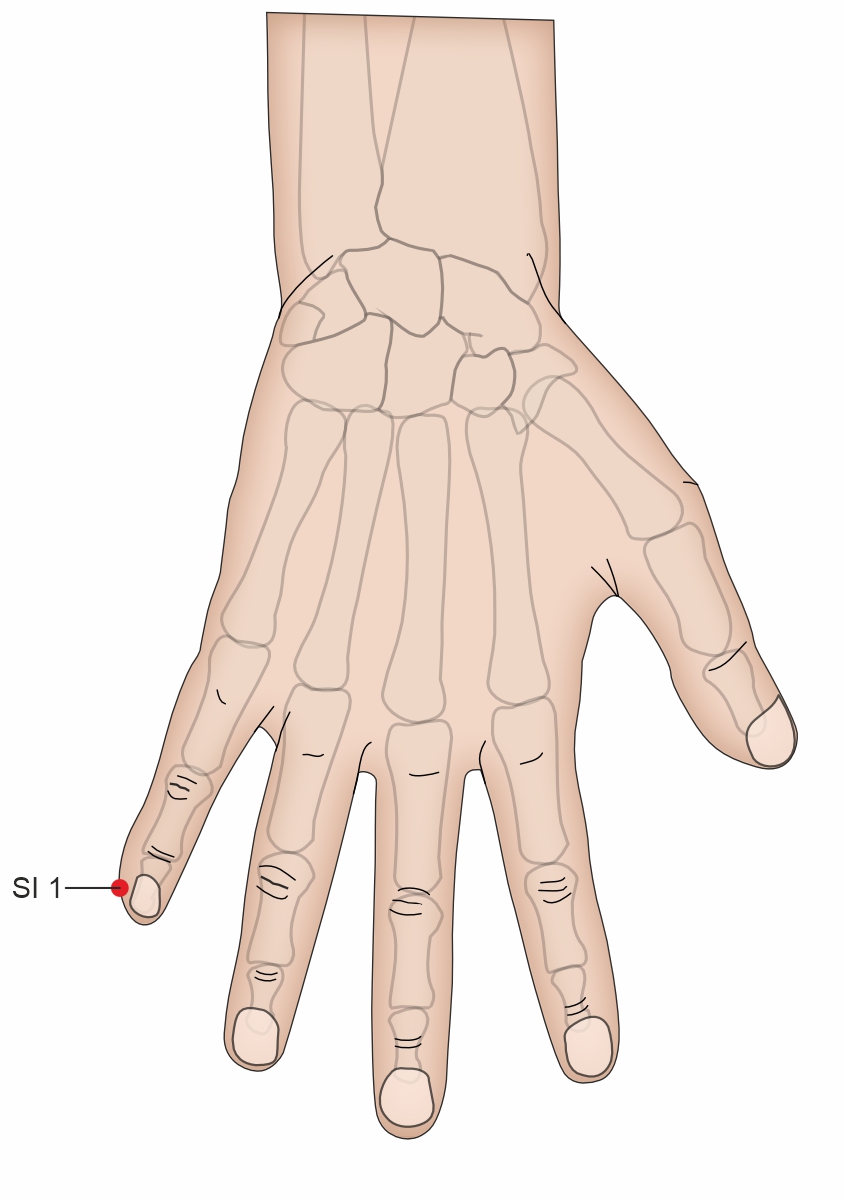

The Small Intestine Meridian begins at the pinky finger, specifically at the corner of the nail on the ulnar side. This first point is called Small Intestine 1 (SI-1).

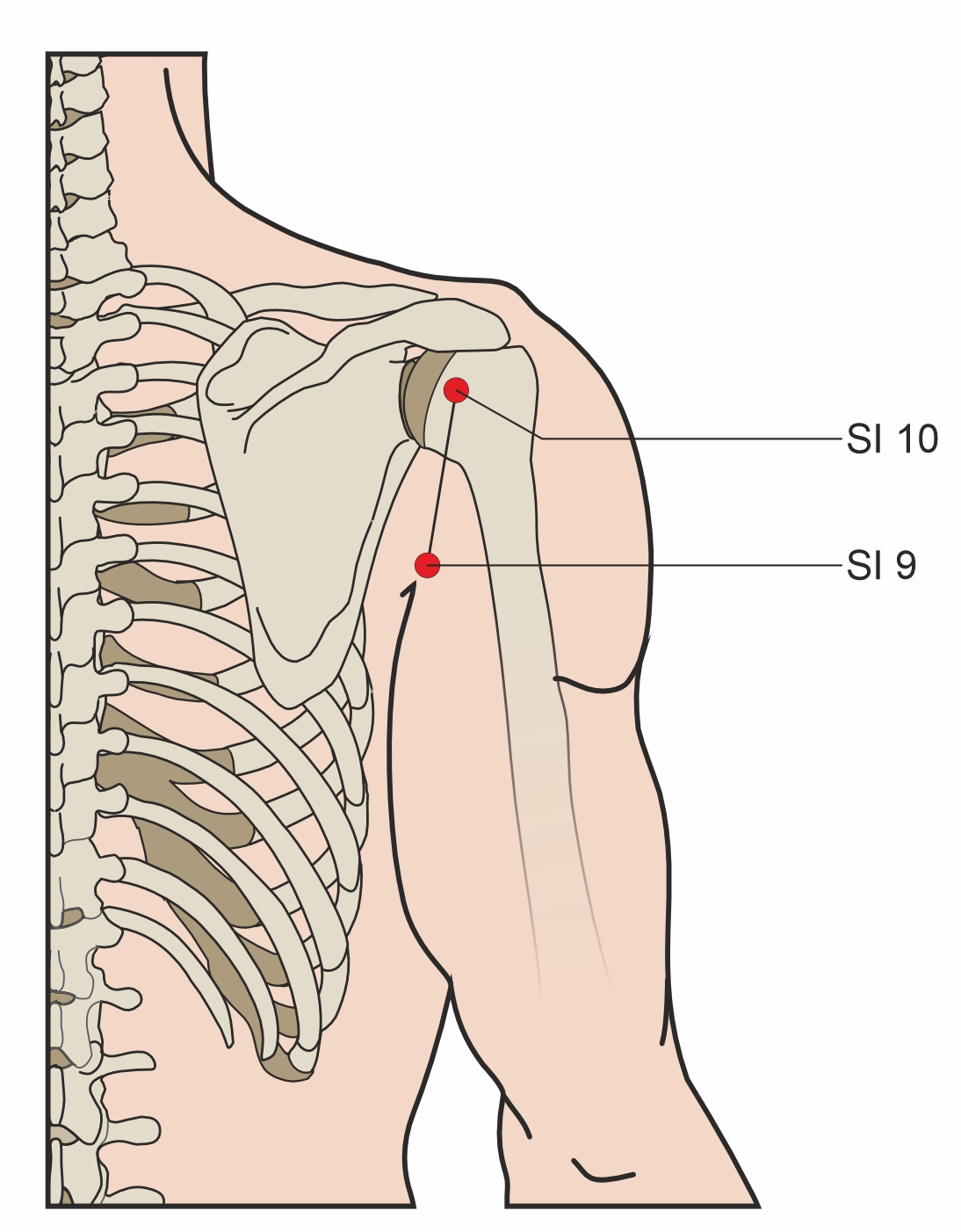

From there, the meridian runs along the ulnar side of the hand, continuing upward along the medial aspect of the forearm. It then passes just medial to the elbow and continues up the medial posterior aspect of the upper arm, reaching the posterior shoulder. It arrives at Small Intestine 10 (SI-10), located just under the lateral aspect of the scapular spine—you can feel this point by lifting your arm.

The Function And Character Of Those Meridians

The Small Intestine Meridian then takes a zigzagging path across the scapular spine along the upper back. After crossing the scapula, it connects with the Du Meridian, which runs down the spinal cord. From there, a branch descends toward the heart, connecting with the Heart Meridian before traveling through the esophagus, diaphragm, stomach, and finally the small intestine.

This anatomical connection is critical in Chinese medicine. The Small Intestine has a close relationship with the Heart, both in function and meridian connection. The pathway traveling from the Small Intestine to the Heart explains their deep interaction in Chinese medical theory.

Now, going back up to the neck region, at the supraclavicular fossa, another branch ascends along the lateral side of the neck, just posterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. From here, the meridian divides into two final branches:

- One branch travels to the infraorbital region, reaching the lateral side of the nose and inner canthus, where it connects with the Urinary Bladder Meridian.

- The second branch, which is particularly relevant to TMJ dysfunction, travels along the outer canthus of the eye, moves posteriorly toward the ear, and finally ends at Small Intestine 19 (SI-19).

Notice how the Small Intestine Meridian connects multiple organ systems—the Heart, the Urinary Bladder, and various structural components along its path. This demonstrates how meridians operate internally within organ systems and externally on the body’s surface. Through acupuncture points, we can influence internal organs based on their external meridian pathways.

Additionally, the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is not an isolated structure in Chinese medicine. The qi and blood that supply the joint come from multiple meridian pathways. The Small Intestine Meridian is just one example, but imbalances along its path can affect TMJ function. Other key meridians, including the Gallbladder, San Jiao, and Stomach channels, also play roles in jaw health.

This interconnected system reveals the complexity of TMJ dysfunction—even something seemingly straightforward involves multiple meridian interactions. Understanding these pathways allows practitioners to diagnose and treat TMJ issues holistically in Chinese medicine.

Why TMD Symptoms Occur in TCM

Now that we have a basic understanding of some of the key principles of Chinese medicine in relation to physiology, I want to zoom in and discuss the symptoms of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction and how they are explained from a Chinese medicine perspective. I’ll go through some common symptoms of TMJ dysfunction and provide examples of underlying issues in Chinese medicine that may contribute to these symptoms. Of course, these are just examples—the actual variations in disease processes and the number of symptoms a patient may experience are numerous and diverse.

One of the most common symptoms of TMJ dysfunction is jaw pain or tenderness. This discomfort can occur near the joint itself or along the jawline. Oftentimes, jaw pain and tenderness are related to what we call Qi or blood stasis. This means there is poor flow of Qi or blood through the meridian pathways. When circulation becomes stagnant, the joint and surrounding jaw structures do not receive sufficient nourishment, leading to pain. Blood and Qi are essential for maintaining smooth movement, bone health, marrow quality, and muscle function, so when their flow is disrupted, discomfort can arise.

Another common symptom of TMJ dysfunction is clicking, popping, or grating sounds in the joint. While this could stem from several different issues, one contributing factor seen in Chinese medicine is improper water metabolism. When the body’s fluid regulation is imbalanced, it can sometimes manifest as abnormal joint sounds. Additionally, clicking and popping noises may be linked to kidney health, as the kidney system plays a role in bone and joint integrity.

A third symptom of TMJ dysfunction is difficulty chewing or pain while chewing. Some patients report feeling that their jaw is stiff or misaligned. In Chinese medicine, this issue may stem from imbalances in the stomach and large intestine meridians. These two organs are closely related, and disruptions in their harmony—whether from excess or deficiency—can contribute to misalignment and dysfunction in the jaw.

Some patients with TMJ dysfunction also experience headaches, particularly on the lateral side of the head, above the ear, and near the TMJ area. These headaches are often associated with the gallbladder meridian. If headache pain in this region is a prominent symptom, the gallbladder organ and its meridian may be implicated as an underlying cause.

Treatment

In Chinese medicine, the treatment of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders primarily involves acupuncture and herbal medicine. These are the two primary modalities I use in my clinic, and I want to emphasize that the examples provided are illustrative of treatment principles, rather than fixed prescriptions for every case. Understanding how we think about the body’s imbalances and the rationale behind point selection is more important than memorizing specific protocols. First, let’s explore acupuncture, then we’ll dive into some herbal approaches.

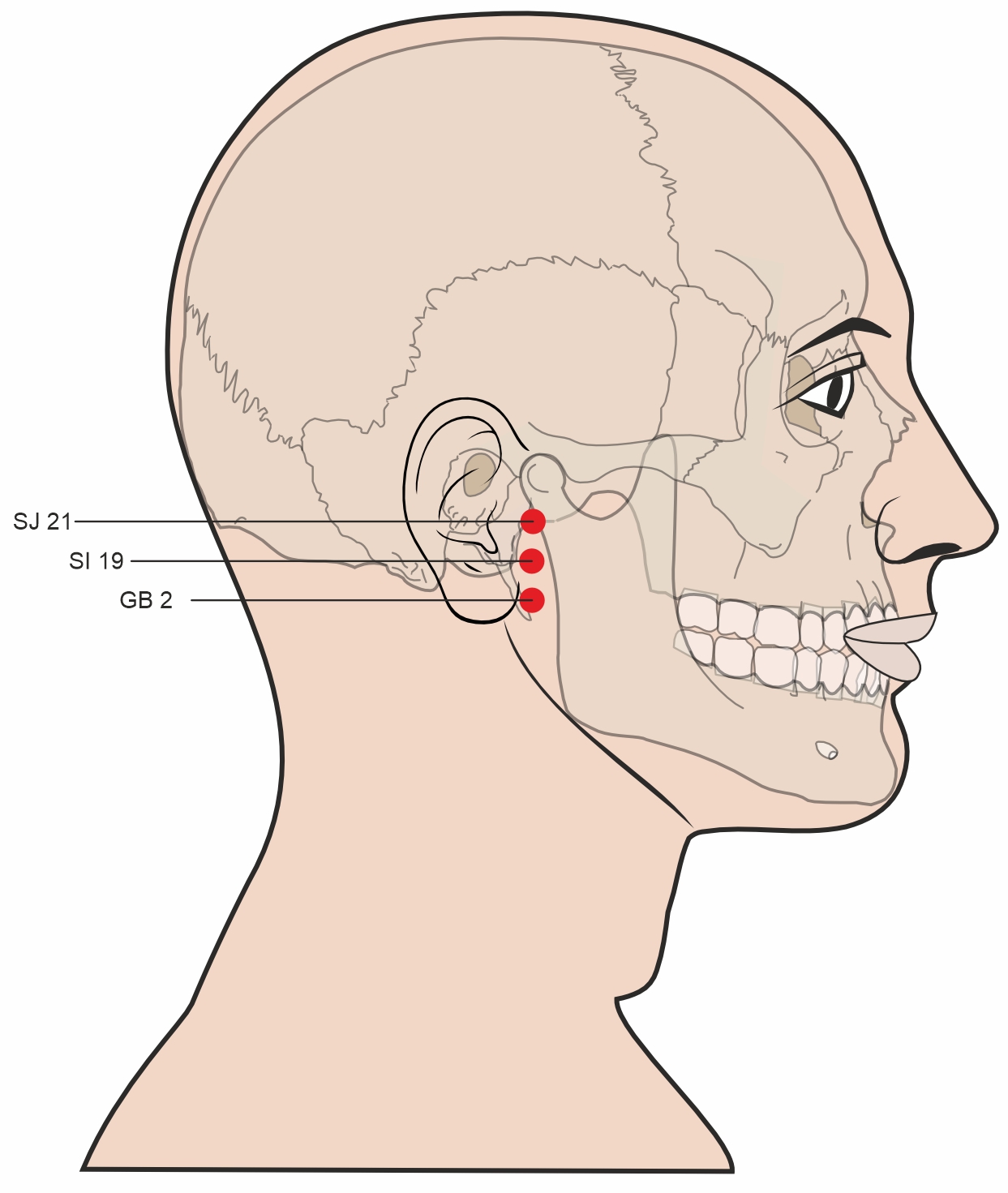

When using acupuncture for TMJ, we stimulate superficial points along the body to influence internal organ function and correct imbalances that contribute to TMJ symptoms. One crucial point is Small Intestine 19 (Ting Gong), which translates to “Auditory Palace.” This point is located between the tragus and the mandibular joint and can be found by asking the patient to slightly open their mouth—revealing a small depression where the mandibular condyle shifts forward. Ting Gong is the final point on the Small Intestine meridian, and it also connects with two neighboring meridians: Gallbladder 2 (Ting Hui, located just below it) and San Jiao 21 (Er Men, located just above it). Together, these three points influence the ear, jaw, and neuromuscular function of the temporomandibular region.

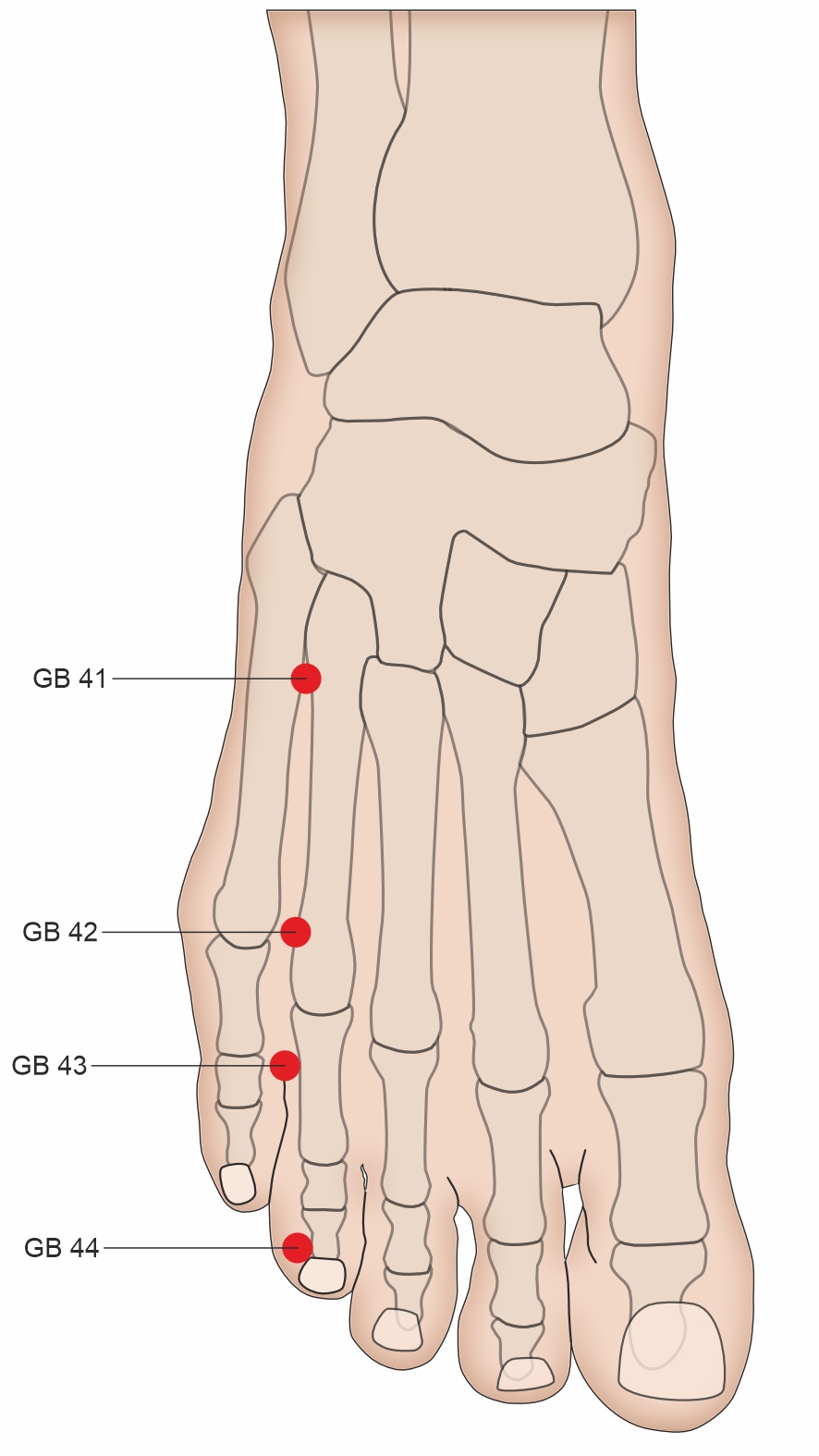

Beyond local points, a distal acupuncture pairing often used for TMJ involves San Jiao 5 (Waiguan) and Gallbladder 41 (Zulinqi). San Jiao 5, located two cun above the wrist crease on the forearm, is the Master Point of the Yang Wei Vessel, allowing it to regulate Yang energy and support the Gallbladder meridian. Gallbladder 41, found on the dorsal aspect of the foot between the fourth and fifth metatarsal bones, works synergistically with San Jiao 5. Since both points belong to meridians that converge at the TMJ region, this pairing effectively addresses jaw tension, headaches, and energetic blockages contributing to discomfort in the temporomandibular joint.

Herbs

Let’s take a few minutes to talk about herbal treatment options for temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction. I’ve been emphasizing that TMJ dysfunction can stem from a wide variety of underlying issues. Often, it is intertwined with imbalances in the small intestine, Sanjiao, or gallbladder meridian, though it can also involve other systems.

For illustrative purposes, I’m going to highlight one herbal formula that may help in certain cases and explain how it works. Keep in mind—this formula is not a universal solution for all TMJ cases. But if it matches your particular pattern, it might be a treatment option for you.

The formula I’m focusing on is called Du Huo Ji Sheng Tang. Written in 650 A.D., this ancient formula appears in a famous Chinese medical text: Important Formulas Worth a Thousand Gold Pieces.

This is a complex formula containing 15 different herbs, each with unique properties. The overarching purpose of Du Huo Ji Sheng Tang is to dispel wind and dampness—two pathogenic factors that can lead to disease. It is traditionally used to relieve pain symptoms, but it can also help TMJ dysfunction when the condition stems from excess wind and dampness, compounded by weakness in the Liver and Kidney systems.

While this formula contains 15 herbs, let’s highlight two that appear in its name:

- Du Huo (Pubescent Angelica Root) – This is the primary herb in the formula, known for dispelling wind and dampness and clearing cold from the body.

- Sang Ji Sheng (Taxillus or Mistletoe) – This herb also helps clear wind and dampness, but it primarily strengthens the Liver and Kidney, supporting joint and bone health.

I would not advise purchasing this formula and taking it on your own. TMJ dysfunction varies from patient to patient, and treatment must match the root cause. Even if I were to prescribe Du Huo Ji Sheng Tang in a clinical setting, I would almost certainly modify it to better suit each individual’s condition.

One of the core principles of Chinese medicine is recognizing the uniqueness of every patient. Not all cases of TMJ dysfunction are alike, and prescribing any herbal formula requires deep understanding of how each ingredient interacts within the body. Adjusting the formula—whether adding or removing herbs—can significantly change its effect.

If you’re considering TCM treatment for TMJ dysfunction you need to consult a qualified practitioner who can assess your specific pattern of imbalance and create a personalized approach.

Clinical Trial

The last thing I want to talk about today is a study published in 2024 in QJM: International Journal of Medicine, examining the use of acupuncture for temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction. The title of this article is “Effect of acupuncture for temporomandibular disorders: a randomized clinical trial.” This trial focused on two key questions: Can acupuncture help reduce pain intensity? And can it improve jaw function compared to sham acupuncture?

The researchers randomized 60 participants with TMJ dysfunction, assigning them in a 1:1 ratio to receive either real acupuncture or sham acupuncture (which mimics acupuncture but doesn’t have therapeutic effects). Each participant underwent three sessions per week for four weeks, with each session lasting 30 minutes.

The primary outcome measured was the change in weekly pain intensity from baseline to week four and week eight. The results? The real acupuncture group experienced greater pain relief at both four and eight weeks. Not only that, but their jaw mobility and function significantly improved as well.

Interestingly, the study also tracked psychological well-being, using the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS), and sleep quality, assessed with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). The acupuncture group showed improvement in these areas too.

The researchers concluded that acupuncture is an effective treatment for TMJ dysfunction, reducing pain and enhancing both physical and emotional function. The benefits lasted at least eight weeks—without the use of medications.

While traditional Chinese medicine has recognized acupuncture’s benefits for thousands of years, it’s encouraging to see modern research validating these principles in mainstream medical literature.

That’s all for today! I hope this gave you a better understanding of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction and how we approach its treatment from an Oriental medicine perspective—especially how I see it from my own experience and practice.

If you found this helpful, let us know in the comments! If you’d like more information about what we do, visit houstonacupuncture.com, and don’t forget to subscribe to stay in the loop on future discussions about health, disease, and Oriental medicine.

See you next time!

Liu, L., Chen, Q., Lyu, T., Zhao, L., Miao, Q., Liu, Y., Nie, L., Fu, F., Li, S., & Zeng, C. (2024). Effect of acupuncture for temporomandibular disorders: A randomized clinical trial. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 117(9), 647–656. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcae094

- Unlocking the Mystery of Jaw Pain: Understanding Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD) - September 18, 2025

- Finding a Licensed Acupuncturist in Houston - November 20, 2024

- Can Acupuncture Help with Weight Loss - October 28, 2024